Ambulance delays – why ‘more paramedics’ is only a short-term fix

The pandemic has highlighted chronic health system challenges, including ‘ramping’ – the often long wait in transferring patients from paramedics to emergency departments. With her unique perspective as an actuary and paramedic, Sophie Dyson explains how a system-wide approach is needed to find lasting solutions to ambulance delays.

While I was working as a paramedic in Sydney last month, a man pulled up next to our parked ambulance and asked, if he went home and called Triple Zero, could an ambulance take him to a particular hospital his doctor had instructed him to go to. I wondered why he couldn’t simply continue driving to his destination. He explained he wanted to call an ambulance because parking at the hospital was difficult.

At a time when demand for ambulances is at an all-time high, this behaviour is frustrating. Ambulance ‘ramping’ was a central issue to the recent Labor victory in South Australia, but ambulance workload and response performance is a perennial story that pre-dates the pandemic.

“Paramedics unable to respond to emergencies … or callers unable to get through to Triple Zero … are indicators that something is wrong”

Paramedics unable to respond to emergencies because they’re waiting at hospital, or callers unable to get through to Triple Zero operators because of high demand, are visible and emotive indicators that something is wrong. Increasing ambulance capacity is only a short-term fix. Ambulance services are an integral part of the health system, and a system approach is needed to find a solution.

Ramping – a system problem

Ambulance ramping refers to paramedics being delayed in handing over care of their patients to the emergency department (ED). On arrival at ED, paramedics take patients into the ambulance bay to be triaged by the ED nurse. If there is no ED bed or treatment chair available and the patient cannot safely be transferred to the waiting room, paramedics must wait with their patient, making them unavailable to respond to other emergencies. The consequent reduction in ambulance response capacity lengthens response times.

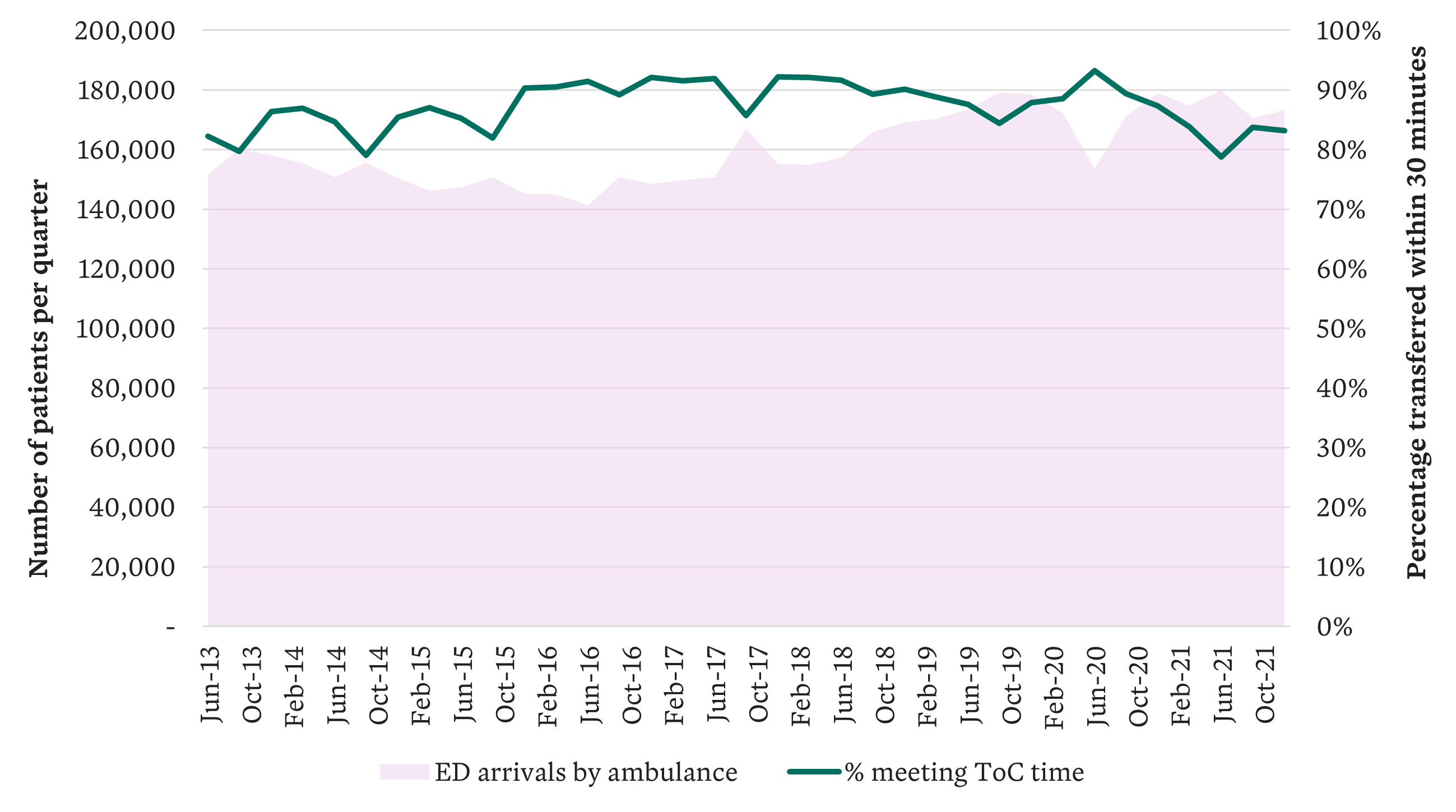

Target times for transfer of care (ToC) from paramedics to EDs vary between states. In NSW, the target is 90% within 30 minutes, but during busy periods, ToC times can extend to several hours. As you would expect, as ED workloads rise, the proportion of patients transferred from paramedic to ED care within the target ToC time falls. The following graph shows the number of patients brought to EDs in NSW by ambulance between 2013 and 2021 compared with the proportion of patients meeting the ToC target.

Ambulance arrivals vs % of patients meeting ToC target (NSW), which can extend several hours

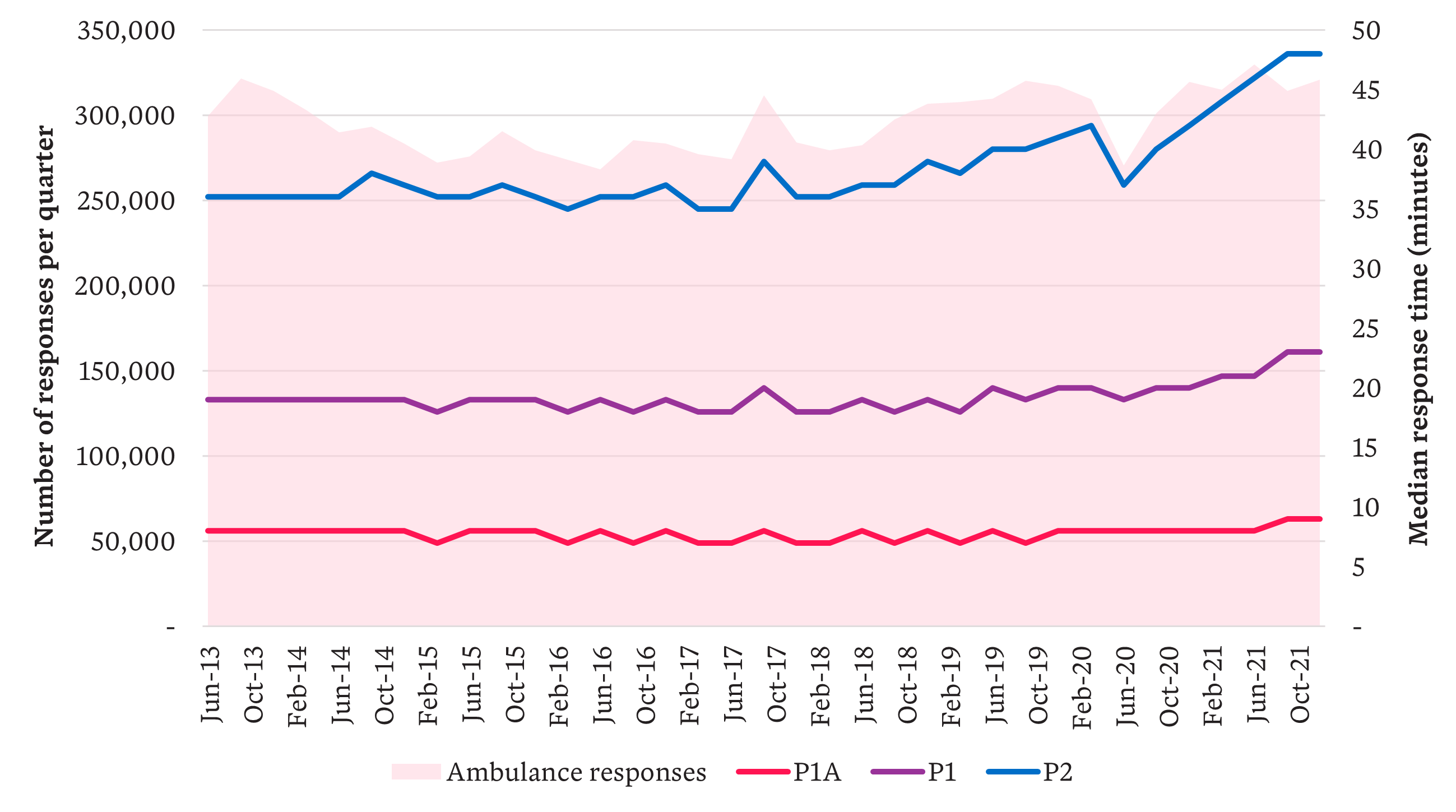

The relationship between ambulance workload and response performance is also clear in this next graph. Each state determines its own response priorities. In NSW, for example, the most urgent category is Priority 1A (P1A), all Priority 1 (P1) incidents get a lights and sirens response, and Priority 2 (P2) represents lower urgency incidents. The deterioration in response performance as ambulance workload increases is seen most dramatically in P2 median response times, as the ability to reassign vehicles to higher priority incidents has a protective effect on P1 and P1A response performance.

Ambulance responses vs response times by priority (NSW) – a dramatic deterioration in P2

Why are ambulance delays a system problem? Almost nine million people a year present to Australian EDs. Paramedics are delayed transferring patients from ambulance to ED because EDs are full, from the 25% of patients brought in by ambulance and the 75% who arrive by other means. EDs can’t free up beds until patients are treated and discharged from ED, or transferred to a hospital ward (Australia-wide, a little more than 30% of ED presentations are admitted to hospital). The barrier to transferring patients from ED to wards is that the wards are full, and the barriers to discharging patients from wards include waiting for aged care or disability services, or patient transport. Downstream capacity and patient flow are the system issues here.

Financial incentives and convenience driving ambulance delays

System interrelationships exist on the demand side too, with evidence of overlapping needs in demand for ambulances, ED treatment and the 38,000 GPs providing primary care in the community. Government data shows that across all Australian jurisdictions, ambulance services responded to three million Triple Zero incidents in 2020-21, of which 50% did not require an emergency (lights and sirens) response and 25% of patients were able to be treated and left at home, referred to their GP or another healthcare provider. In EDs, one-third of patients were deemed ‘potentially avoidable GP-type presentations’.

This situation is driven by financial incentives and convenience. For example, although ambulance services are not funded by Medicare, for most patients – those with pension cards, private health insurance or an ambulance membership – ambulance care is free at the point of care and there are no financial consequences for calling Triple Zero. The cost, almost $1,100 per incident, falls largely on state governments. For low-acuity incidents, that’s a lot to pay for reassurance and a couple of paracetamol.

“In 2020-21 … one-third of [emergency department] patients were deemed ‘potentially avoidable GP-type presentations’ ”

Ambulance services recognise the issue of ambulance/ED/primary care substitution and the market failure this represents. Several services have developed initiatives to address the high cost of dispatching an ambulance to low-acuity calls while at the same time providing more clinically-appropriate care – these initiatives include virtual care programs that provide telephone advice and referrals to other providers. The cost of providing virtual care, even with an ultimate referral to a private medical provider, is less than half that of sending an ambulance. Heightened demand during COVID-19 has resulted in an expansion of these services. From an ambulance perspective, they demonstrate an entirely rational response. However, from a whole-of-system perspective, the cost to government is still several multiples of what would be paid via Medicare for a telehealth consultation with a GP.

Where can we look for a solution?

The pandemic has been a time of innovation in healthcare delivery. Telehealth, originally introduced to support service provision in rural areas, has become the default method for talking to our family doctor. Smartphone apps record COVID-19 patients’ vital signs and detect early indicators of deterioration. Algorithms predict the COVID-19 patients most at risk of hospitalisation and target patient monitoring resources more effectively.

With light at the end of the COVID-19 tunnel, we need to sustain the spirit of innovation and action to develop longer-term solutions to ambulance ramping (and other health-system problems while we’re at it). To do this, both demand and supply issues need to be tackled, as well as improving patient flow and care coordination.

“Demand and supply issues need to be tackled, as well as improving patient flow and care coordination”

Australia’s health system delivers an enviable level of care, but overlapping state and Commonwealth responsibilities have always created opportunities for blame- and cost-shifting. The rapid introduction of certain COVID-19 initiatives has exacerbated this situation, with similar services accessible through different pathways and a blurring of health-service responsibilities.

Navigating a whole-of-system approach

When developing future solutions, we need to remove duplication and substitution, consider solutions through a whole-of-system lens rather than from the perspective of a single provider, and recognise the financial and other incentives that drive healthcare demand and supply.

Back to the driver who wanted to call Triple Zero to overcome the inconvenience of parking. Consider the financial impact of lost revenue if hospital parking for ED attendances was subsidised, compared with the savings from reducing the unnecessary dispatch of ambulances. How could these savings be applied to expand service delivery and provide more appropriate clinical care?

Next time ambulance ramping is in the news, don’t think ‘we need more paramedics’ (though that’s always a welcome thought) to solve ambulance delays, think ‘we need to capitalise on COVID-19 ingenuity, develop sustainable solutions addressing both demand and supply, and take a whole-of-system view that recognises financial and other incentives’. Even though it doesn’t make a catchy soundbite.

Related articles

Related articles

More articles

Increase in Australians with disability – new ABS survey

New data shows a significant rise in the number of people who report having a disability. We discuss the findings and offer key takeaways

Read Article

What climate disclosure means for the public sector

Following up our article on climate disclosures for insurers, we look at the latest developments for government entities across Australia

Read Article